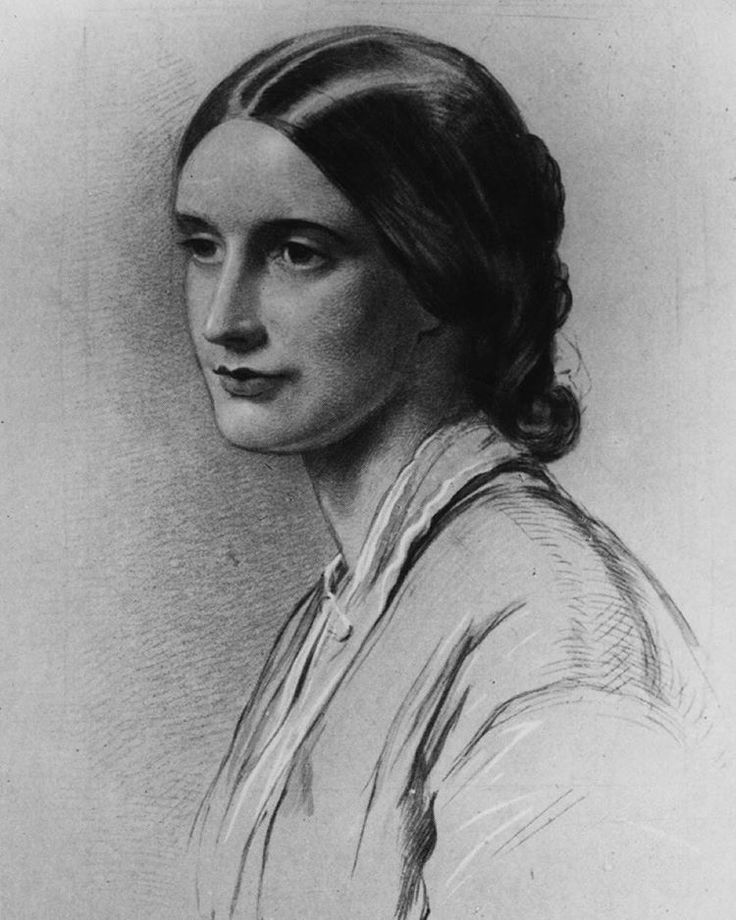

Josephine Butler

Josephine Elizabeth Butler (1828-1906) was an English feminist and social reformer. She campaigned for women's suffrage, the right of women to better education, the end of coverture in British law, the abolition of child prostitution, and an end to human trafficking of young women and children into European prostitution.

Josephine

Grey was born on 13 April 1828 in Northumberland. She was the fourth daughter

and seventh child of Hannah (née Annett) and John Grey, a land agent and

agricultural expert, who was a cousin of the reformist British Prime Minister,

Lord Grey. In 1833 John was appointed manager of the Greenwich Hospital Estates

in Dilston, where John acted as Lord Grey's chief political agent. In this role,

John promoted his cousin's political opinions locally, including support for

Catholic emancipation, the abolition of slavery, and reform of the poor laws.

Josephine completed her schooling at a boarding school in Newcastle upon Tyne.

John treated

his children equally within the home, educating them all in politics and social

issues, and introducing them to politically important visitors. John's

political work and ideology had a strong influence on his daughter, as did the

religious teaching she received from her mother. Thus, she grew up surrounded

by those with a strong social conscience and a staunch religious faith.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

“I spoke to

Him in solitude, as a person who could answer... Do not imagine that on these

occasions I worked myself up into any excitement; there was much pain in such

an effort, and dogged determination required. Nor was it a devotional sentiment

that urged me on. It was a desire to know God and my relation to Him.”

Around the

age of 17 Grey went through a religious crisis, probably caused by discovering

the body of suicide victim while out riding. She became disenchanted with her

weekly church attendance, describing the local vicar as "an honest man in

the pulpit ... [who] taught us loyally all that he probably himself knew about

God, but whose words did not even touch the fringe of my soul's deep

discontent". Following her crisis, Grey did not identify with any single

strand of Christianity, and remained critical of the Anglican church. She later

wrote that she "imbibed from childhood the widest ideas of vital

Christianity, only it was Christianity. I have not much sympathy with the

Church". She began to speak directly to God in her prayers.

In mid-1847

Grey visited her brother in Ireland at the height of the Great Famine. Here she

witnessed firsthand the rampant suffering of the poor. She was deeply affected

by her experiences and later recalled that: "As a young girl, I had no

conception of the full meaning of the misery I saw around me, yet it printed

itself upon my brain and memory."

--------------------------------------------------------

By 1850,

Grey had grown close to George Butler, a Fellow of Exeter College, Oxford, whom

she had met at several balls and who sent her poetry frequently. The couple became

engaged in January 1851 and married a year later. They set up home at 124, High

Street, Oxford. George was a scholar and cleric and shared with his wife a

commitment to liberal reforms and a strong Christian belief. She later wrote

that they often "prayed together that a holy revolution might come about

and that the Kingdom of God might be established on the earth".

In November

1852 the Butlers had a son, George Grey Butler, followed by a second, Arthur Stanley—known

as Stanley—in May 1854. Butler's later memories of Oxford were of a closeted

and misogynist community lacking in family life; she was often the only female

at social gatherings and would listen in anger to "the open acceptance of

the double standard by the gentlemen of the university". She was disgusted

that the male conversationalists considered it natural that a "moral lapse

in a woman was spoken of as an immensely worse thing than in a man". She

conseuqnetly made the wise decision "to speak little with men, but much

with God". As a more practical measure she—and George—began to help many

of the “fallen woman” of Oxford and invited some to live in their home. One

case in which they were involved concerned a young woman serving a prison

sentence at Newgate Prison. The woman had been seduced by a university don who

had subsequently abandoned her and the woman had murdered her baby in despair.

By 1856

Oxford's damp atmosphere had exacerbated a long-standing lesion on Josephine’s

lung; her doctor informed her that to remain in Oxford could be fatal. George

purchased a house in Clifton, near Bristol, where their third son, Charles, was

born in 1857. George took the position of vice-principal at Cheltenham College

and they moved to a local house. They continued their support for liberal

causes, making them unpopular with their peers; Butler described the resultant

feeling of social isolation as “often painful ... but the discipline was

useful".

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In May 1859

Butler gave birth to her final child, a daughter, Evangeline Mary, known as

Eva. When she was just 5 years old, Eva fell 40 feet from the top-floor banister

onto the stone floor of the hallway in her home. She died three hours later.

Butler was distraught at the loss. She could not sleep properly or discuss the

circumstances of her daughter’s death for 30 years.

In October

1864 Stanley contracted diphtheria. Butler herself was suffering rom depression

and was in poor physical health. Once the worst of Stanley's ailment passed,

Butler decided to take him to Naples so they could both recuperate. However,

their ship was rocked with bad weather and Butler had a physical breakdown on

board which she was lucky to survive.

In January

1866 George was appointed headmaster of Liverpool College, and the family moved

to the Dingle area. Butler continued to mourn for Eva, but focused her energy

on helping others; she later wrote that she "became possessed with an

irresistible urge to go forth and find some pain keener than my own, to meet

with people more unhappy than myself. ... It was not difficult to find misery

in Liverpool." She made regular visits to the 5000-strong workhouse at

Brownlow Hill where she would sit with the women in the cellars—many of whom

were prisoners—and pick oakum with them, praying alongside them and educating

them on the Bible.

Again, the

Butlers began providing shelter in their home for women, often prostitutes in

the terminal stages of venereal disease. It soon became clear that there were

more women in need than they could provide for, so Butler set up a hostel, with

funds from wealthy locals. By Easter 1867 she had established a second, larger

home, in which more appropriate work was provided, such as sewing and the

manufacture of envelopes; the "Industrial Home", as she called it,

was funded by the workhouse committee and local merchants.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Butler constantly

ampaigned for women's rights, including the right to the vote and to have a

better education. In 1866 she was a signatory on a petition to amend the Reform

Bill to widen the franchise to include women. The petition, which was supported

by the MP and philosopher John Stuart Mill, was ignored.

Butler

considered her hostels a temporary measure; she firmly believed that women

would always struggle until they had the education to improve their prospects. In

1867, with the suffragist Anne Clough, she established the North of England

Council for Promoting the Higher Education of Women, which aimed to raise the

status of governesses and female teachers to that of a profession; She served

as its president until 1873. A series of lectures, initially in towns in the

north of England, began under James Stuart, a Fellow of Trinity College,

Cambridge. They hoped to lecture to 30 students – instead, 300 signed up. In

1868 Butler published her first pamphlet, "The Education and Employment of

Women", in which she argued for access to higher education for women, and

more equal access to a wider range of jobs. It was the first of 90 books and

pamphlets she authored. She and Clough successfully petitioned the senate of

the University of Cambridge to provide examinations for women; the Cambridge

Higher Examination for women was introduced the following year. I have friends

at the UoC now, and its crazy to think that without women like Butler they

never would’ve had that right.

In Victorian

Britain, marriage law was based on the legal doctrine of coverture, in which a

woman's legal rights and obligations were subsumed by those of her husband upon

their marriage. Legally, women had no separate legal existence, and all her

property became her husband's. It was nigh impossible for a woman to initiate

divorce. In April 1868 Butler and fellow suffragist Elizabeth Wolstenholme set

up and became joint secretaries of the Married Women's Property Committee to

pressure parliament into changing the law. Butler remained on the committee

until the campaign was successful in achieving the passing into law of the

Married Women's Property Act 1882.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In 1869

Butler became aware of the Contagious Diseases Acts which had been introduced

in 1864, 1866 and 1869 to regulate prostitution in an attempt to control the

spread of venereal diseases, particularly in the British armed force. The Acts

authorised police in certain areas to detain and inspect women considered to be

prostitutes— with no evidence or justification needed save the policeman’s suspicions.

If a magistrate agreed, women were given painful and intrusive genital

examinations. If women were suffering from sexually transmitted diseases, they

were held in a lock hospital until the condition was cured. If they refused to

be examined or hospitalised they could be imprisoned, often with hard labour.

Units of

plain-clothed policemen specialised in arresting suspected prostitutes, "hated

for their surveillance and harassment of prostitutes and working-class women

... who they treated with little regard for their legal rights". Women who

were subjected to the examination found their names and reputations ruined.

Thus, ironically, "the Acts had the

effect of turning them to prostitution by barring respectable ways of life to

them".

In September

1869, Wolstenholme and Butler met in Bristol to discuss what could be done

about the Acts. The National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious

Diseases Acts was founded that October but women were not permitted to join

(sigh). Consequently, Wolstenholme and Butler formed the Ladies National Association

for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts (LNA). The LNA published a

Ladies Manifesto, which stated that the Acts were discriminatory on grounds of

both sex and class; the Acts, it was claimed:

“not only

deprived poor women of their constitutional rights and forced them to submit to

a degrading internal examination, but they officially sanctioned a double

standard of sexual morality, which justified male sexual access to a class of

'fallen' women and penalised women for engaging in the same vice as men.”

On 31

December 1869 the Ladies National Association published a statement in The

Daily News that it had "been formed for the purposes of obtaining the

repeal of these obnoxious Acts". Among the 124 signatories were the social

theorist Harriet Martineau and the social reformer Florence Nightingale.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In 1870, Butler

toured Britain, travelling 3,700 miles to attend 99 meetings. She focused her

attention on working-class family men, the majority of whom were outraged at

the description Butler gave of the examination women were forced to undergo (a

process she called “surgical or steel rape”). Although she persuaded many

members of her audiences, she faced significant and dangerous opposition.

Incidents she faced included being pelted with cow dung by pimps, having her

windows smashed, and others threatening to burn down the building during her

lectures. Despite the personal risk, Butler carried on.

At the 1870

Colchester parliamentary by-election, the LNA fielded a candidate against the

Liberal Party candidate Sir Henry Storks, a supporter of the Acts. Butler held

several local meetings during the campaign; during one, she was chased by a

group of brothel owners. The presence of the LNA candidate split the Liberal

vote and allowed the Conservative Party candidate to win the seat. Nonetheless,

Butler considered this “somewhat of a turning-point in the history of our

crusade". Stork's loss prompted the

Home Secretary, Henry Bruce, to launch a Royal Commission to examine the

situation. One MP told Butler that

“Your

manifesto has shaken us very badly in the House of Commons; a leading man in

the House remarked to me, "We know how to manage any other opposition in

the House or in the country, but this is very awkward for us—this revolt of the

women. It is quite a new thing; what are we to do with such an opposition as

this?"

The

commission began work in early January 1871 and spent six months taking

evidence. After Butler testified on 18 March, a member of the committee,

Liberal MP Peter Rylands, stated: "I am not accustomed to religious

phraseology, but I cannot give you an idea of the effect produced except by

saying that the spirit of God was there". Nevertheless, the commission's

report defended the one-sided nature of the legislation, saying "... there

is no comparison to be made between prostitutes and the men who consort with

them. With the one sex the offence is committed as a matter of gain; with the

other it is an irregular indulgence of a natural impulse." (I might

actually be sick). The report accepted the findings that the sexual health of

men in the 18 areas covered by the Acts had improved. In relation to the compulsory

examinations, the commission was swayed by the descriptions of "steel

rape", and suggested it should be voluntary not compulsory. The commission

heard significant evidence that many prostitutes were as young as 12 and

recommended that the age of consent should be raised from 12 to 14 (woopty doo).

Bruce took no action on the recommendations for six months.

In February

1872, Bruce finally proposed a bill that took some of the commission's

recommendations, but widened the geographical scope from the 18 military

centres to the whole of the UK. Although the LNA's initial stance was to accept

some of the bill's clauses and try and change others, Butler rejected it in its

entirety and published The New Era, a 56-page pamphlet attacking the legislation.

Sadly, she lost many personal supporters because of her stance. The bill faced

too much opposition from the parliamentary supporters of the Contagious

Diseases Acts, and was withdrawn.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Butler

continued to face violent opposition – which was watched calmly by the

Metropolitan police who did little to intervene. In December 1872 Butler met the Prime

Minister, William Gladstone, when he visited Liverpool College. Although he

supported the aims of the LNA, he was politically unable to back the LNA

publicly, and had supported Bruce's bill.

The fall of

the Liberal government in 1874, and its replacement with Benjamin Disraeli's

Conservative administration meant that the repeal campaign stalled; Butler

called it a "year of discouragement" when there was "deep

depression in the work". Although the LNA kept up the pressure, progress

in persuading Liberal MPs to oppose the Contagious Diseases Acts was slow, and

the government was unrelenting in its support for the Acts.

At a meeting

of regional LNA branches in May, one speech focused on legislation in Europe

and the LNA resolved to work with its sister organisations across Europe. In

December 1874 Butler left for Paris, touring France, Italy and Switzerland,

where she met with local pressure groups and civic authorities. As in Britain,

she encountered strong support from feminist groups, but hostility from the

authorities. She returned from her travels at the end of February 1875.

As a result

of her experiences, in March 1875 Butler formed the British and Continental

Federation for the Abolition of Prostitution (later renamed the International

Abolitionist Federation), an organisation that campaigned against state regulation

of prostitution and for "the abolition of female slavery and the elevation

of public morality among men" (LOL, still waiting two centuries later). The

Liberal MP James Stansfeld—who wished to repeal the Acts—became the

federation's first general secretary; Butler became joint secretary.

In 1878

Josephine wrote a biography of Catherine of Siena, which historians argue

provided "historical justification for her own political activism". Her

biographer, Helen Mathers, believes that "in emphasising that she and

Catherine were born to be leaders, of both men and women, ... [Butler] made a

profound contribution to feminism".

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Disraeli's

Conservative government lost the general election of 1880 and was replaced by

Gladstone's second ministry, a high proportion of which wanted to repeal the

Contagious Diseases Acts. As Prime Minister, Gladstone had the power to

nominate candidates to vacant positions within the Church and, in June 1882, he

offered George Butler the position of canon of Winchester Cathedral. George had

been considering retirement, but he and Josephine were concerned about their

finances, as much of their income had been spent on the LNA and other causes

Josephine supported. George accepted the appointment, and they moved into a

grace and favour home near the cathedral. Josephine Butler set up another

hostel for women near their home. (We stan a supportive, feminist husband!)

Political

pressure from Liberal backbenchers, particularly Joseph Chamberlain and Charles

Hopwood, led to increasing opposition to the Acts. In February 1883 Hopwood

tabled a resolution in parliament: "That this House disapproves of the

compulsory examination of women under the Contagious Diseases Acts", which

was debated in April. MPs voted by a majority of 72 to suspend the inspections;

three years later the Acts were formally repealed.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Around 1879,

Butler became aware of the slave trade of young women and children from England

to mainland Europe. Young girls were considered "fair game”, as they were

legally allowed to become prostitutes aged 13. After playing a minor role in

starting an investigation into an accusation of trafficking, Butler became

active in the campaign in May 1880, and wrote to The Shield that "the

official houses of prostitution in Brussels are crowded with English minor

girls", and that in one house "there are immured little children,

English girls of from twelve to fifteen years of age ... stolen, kidnapped,

betrayed, got from English country villages by every artifice and sold to these

human shambles".

She visited

Brussels where she met the mayor and local councillors and made allegations

against the head of the Belgian Police des Mœurs and his deputy. After the

meeting she was contacted by a detective who confirmed that the senior members

of the Police des Mœurs were guilty of collusion with brothel keepers. She

returned home and filed a deposition containing a copy of the statement from

the detective and sent them to the Procureur du Roi (Chief Prosecutor) and the

British Home Secretary. Following an investigation in Belgium, the head of the

Police des Mœurs was removed from office, and his deputy was put on trial

alongside 12 brothel owners; all were imprisoned for their roles in the trade

#justice.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In 1885, Butler

met Florence Soper Booth, the daughter-in-law of Salvation Army founder, William

Booth. Booth introduced Butler to a campaign to expose child prostitution in

Britain and its associated trade. Along with Booth, Benjamin Scott the City

Chamberlain and several supporters from the LNA, she persuaded the campaigning

editor of The Pall Mall Gazette, William Thomas Stead, to help their cause.

Stead controversially

decided that the best way to prove that the purchase of young girls for

prostitution took place in London, was to buy a girl himself. Butler introduced

him to a former prostitute and brothel owner who was staying in her hostel. From

a slum in Marylebone, Stead purchased a 13-year-old girl from her mother for

£5, and took her to France. In July 1885 Stead began the publication of a

series of articles entitled "The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon",

exposing the extent of child prostitution in London. In the first article—which

covered six pages of the Gazette—Stead recounted an interview he had with

Howard Vincent, the head of the Criminal Investigation Department:

"But",

I said in amazement, "then do you mean to tell me that in very truth

actual rapes, in the legal sense of the word, are constantly being perpetrated

in London on unwilling virgins, purveyed and procured to rich men at so much a

head by keepers of brothels?" "Certainly", said he, "there

is not a doubt of it." "Why", I exclaimed, "the very

thought is enough to raise hell." "It is true", he said;

"and although it ought to raise hell, it does not even raise the

neighbours."

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

On 16

July—ten days after Stead’s article was published—Butler gave a speech at a

meeting at London's Exeter Hall calling for increased protection for the young

and the raising of the age of consent. The following day she and George left

for a holiday in Switzerland and France. In their absence, a parliamentary bill

from 1883 dealing with the age of consent was re-debated by MPs; the Criminal

Law Amendment Act 1885 was passed on 14 August 1885. The Act raised the age of

consent from 13 to 16 years of age (which it remains today), while the

procurement of girls for prostitution by administering drugs, intimidation or

fraud was made a criminal offence, as was the abduction of a girl under 18 for

purposes of carnal knowledge (crazy that this had to be MADE illegal, like wtf).

The police investigated Stead's purchase, and Butler was forced to cut her

holiday short to return for questioning. Although she avoided all charges,

Stead was imprisoned for three months.

The passing

of the Criminal Law Amendment Act led to the formation of purity societies,

such as the White Cross Army, whose aims were to force the closure of brothels

through prosecution. The societies widened their remit to suppress what they

considered indecent literature—including information on birth control—and the

entertainment provided by the music halls. Butler criticised these purity

societies because of their "fatuous belief that you can oblige human

beings to be moral by force, and in so doing that you may in some way promote

social purity". Her warnings went unheeded by other suffragists, and some,

such as Millicent Fawcett continued to combine their activities in the feminist

movement with the work for the purity societies.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Although the

Contagious Diseases Acts had been repealed in the UK, the equivalent

legislation remained active in the British Raj in India, where prostitutes near

the British cantonments were subjected to regular forced examinations. The

relevant law was contained in the Special Cantonments Acts which had been put

on to a practical footing by Major-General Edward Chapman, who issued standing

orders for the inspection of prostitutes, and the provision of "a sufficient

number of women, to take care that they are sufficiently attractive [*Puke*],

to provide them with proper houses" .

Butler began

a new campaign to have the legislation repealed, comparing the girls to slaves.

After the campaign put pressure on MPs, the widespread publication of Chapman's

orders led to what Mathers describes as "outrage across Britain". In

June 1888 the House of Commons passed a unanimous resolution repealing the

legislation, and the Indian government was ordered to cancel the Acts. To circumvent

the order, the India Office advised the Viceroy of India to instigate new

legislation ensuring that prostitutes suspected of carrying contagious diseases

had to undergo an examination or face expulsion from the cantonment. I could

write a whole book on the damage the British Raj did to Indian women but I

think this is a fitting example.

Towards the

end of the 1880s George's health began to decline, and Butler spent increasing

time caring for him. They holidayed in Naples in 1889, but George contracted

influenza in the 1889–90 pandemic. They returned to Britain but George died on

14 March 1890. Butler suspended campaigning and moved to Wimbledon to stay with

her eldest son and his family.

Butler, now

aged 62, felt she was too old to travel to India, but two American supporters

visited on her behalf and spent four months building a report showing that the

lock hospitals, compulsory examination and use of underage prostitutes—some as

young as 11—were all continuing to operate. The campaign in Britain pushed

again for changes, and Butler spoke at meetings, published pamphlets and wrote

to missionaries in India.

Although

many of Butler's friends and supporters spoke out against British Imperial

Policy, Butler did not. She wrote that because of the work Britain had

undertaken in making slavery illegal, "[w]ith all her faults, looked at

from God's point of view, England is the best, and the least guilty of the

nations" [100% debatable, but ok]. Disappointingly, during the Second Boer

War (1899–1902), Butler published Native Races and the War (1900), in which she

supported British action and its imperialist policy. However, in the book she

took a strong line against the casual racism inherent in her countrymen's

dealings with foreigners, writing:

“Great

Britain will in future be judged, condemned or justified, according to her

treatment of those innumerable, coloured races, heathen or partly

Christianized, over whom her rule extends ... Race prejudice is a poison which

will have to be cast out if the world is ever to be Christianized, and if Great

Britain is to maintain the high and responsible place among the nations which

has been given to her.” Again, not much change in the passing centuries.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

From 1901

Butler began to retire from public life, resigning her positions in the

campaign organisations and spending more time with her family. In 1903 she returned

to live in Northumberland. She died at home on 30th December 1906.

In 1907

Josephine Butler's name was added to the south side of the Reformers' Memorial

in Kensal Green Cemetery, London. The memorial was erected for those "who

had defied custom and interest for the sake of conscience and public

good".

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In 1915 the

LNA merged with the International Abolitionist Federation to form the

Association of Moral and Social Hygiene, which changed its name to the

Josephine Butler Society in 1953. The society still operates, continuing to

campaign for the protection of prostitutes and provide "protection for

women and children who are criminally detained, violently abused or exploited

by others who profit from their prostitution".

Butler was

not only a staunch feminist but a passionate Christian, whose favourite phrase

was "God and one woman make a majority". According to her biographer Walkowitz,

Butler "pushed liberal feminism in new directions, developing theories and

methods of political agitation that directly affected future campaigns for the

emancipation of women". She developed new approaches to campaigning and

moved the debate beyond discussions in middle-class houses to the public forum,

bringing into the political debate women who had never been involved before.

Butler's campaigning, says Walkowitz, "not only reshaped gender, class,

and sexual subjectivities in late Victorian Britain but also informed national

political history and state-building".

Numerous

historians consider the success of the campaign to repeal the Contagious

Diseases Acts to be a milestone in the history of female emancipation. According

to the political historian Margaret Hamilton, the campaign showed that

"attitudes toward women were changing". The feminist scholar Sheila

Jeffreys says that Butler is "one of the bravest and most imaginative

feminists in history", while Millicent Fawcett wrote that she was

"convinced that ... [Butler] should take the rank of the most

distinguished Englishwoman of the nineteenth century". Her unnamed

obituarist in The Daily News considered that Butler's namewill always rank

amongst the noblest of the social reformers, the fruit of whose labours is the

highest inheritance that we have. She fought with enormous courage and

self-sacrifice in a battlefield where she was subjected to the fiercest antagonism ... She never faltered in her

task, and it is to her in supreme that the English statute book owes the

removal of one of the greatest blots that ever defaced it. Her victory marked

one of the great stages of progress of woman to that equality of treatment

which is the final test of a nation's civilization.”

I couldn’t

agree more. I learned about Josephine in a Christian Philanthropy course during

my undergrad and I’ve loved her ever since. Even by today’s standards her views

are incredibly progressive and her courage and justice is an inspiration to me

as much today as it has been to women throughout the Victorian ages and beyond.

Comments

Post a Comment