Princess Sophia Duleep Singh

Sophia Duleep Singh

Finally sharing the story of my

favourite historical woman (a very tough call): Princess Sophia Duleep Singh.

Sophia embodies my three greatest passions (women’s history, religious history,

and Indian history)! I recently did a talk at work on her and wanted to

continue spreading the word about this queen who is left out of the traditional

white-focussed telling of suffragist history. These posts are based on my

presentation and the proposal I did for a PhD on Princess Sophia. Although my PhD

ended up taking a different direction but it is still my mission to make Sophia

Duleep Singh a household name, especially in the UK. This will be a long one,

but I hope you all love her as much as I do!

Sophia Alexandrovna Duleep Singh (1876 – 1948) was a British-Indian suffragette, Punjabi Princess, women’s rights and anti-racism activist, nurse, socialite, and champion dog breeder. Daughter of the last Maharajah of the Sikh Empire, Sophia reconciled her British and Indian identities and worked effortlessly to improve the lives of her countrymen both sides of the ocean. She struggled bravely as a suffragette despite the violence and convictions she faced, fought tirelessly during both World Wars to support Indian troops serving in the British Army, and spoke out against Britain’s treatment of India and Indians despite her close personal connections with the British Royal Family. Sophia was described as the first international celebrity, but her story has been lost among the white-centric narrative of the Suffragette movement in the UK and United States. We urge anyone teaching the women’s emancipation movement to feature women of colour like Sophia who fought equally hard to secure a woman’s right to vote.

Background

Sophia was born on 8 August 1876 and named after her slave grandmother on her mother’s side and her godmother, Queen Victoria. However, in order to understand Sophia’s story we must go back to the days of her grandfather Maharajah Ranjit Singh, Sikh Emperor. Crowned 1801, Ranjit Singh brought unprecedented prosperity and interreligious peace to the Punjab and the Sikh Empire was the last to submit to the British conquest of India. Sophia’s grandmother was Ranjit’s youngest wife, Jind Kaur, a formidable warrior queen who became the primary adversary of the British following the death of her husband (see my previous post on her). Their son Duleep Singh was born in 1838. In 1845, the First Anglo-Sikh War began under the guise of bringing peace to the kingdom following death of Ranjit Singh. On the 10th February 1846, the British won a decisive victory. The new Maharajah Duleep Singh (aged 9) was forced to sign Treaty of Bhyroval, consenting for the British to rule in his name until he turned 16. His mother Jind Kaur was imprisoned (despite international criticism) and Duleep was taken into “protection” of the British. He was cared for in India by a Scottish Doctor, as an English gentleman under Queen Victoria’s strict instruction. He was eventually given permission to visit Victoria in London, and would never return to India.

Victoria was instantly besotted with the 16 year old Maharajah, and he grew up with the Royal Family, adored by British high society. Duleep Singh was given an estate and an allowance, and lived a life of extravagance and decadence protected from scandal by his close friendship with the Prince of Wales.

In 1864, missionaries arranged for Duleep’s marriage to Bamba Muller, the bastard child of a wealthy German merchant and an Abyssinian slave. It was not a happy marriage, and Queen Victoria often expressed concern for Bamba and protected her family even after Duleep Singh fell from favour. Together, Bamba and Duleep welcomed six children; Victor Albert, Frederick Victor, Bamba, Catherine, Sophia, and Edward. Edward died in infancy much to his sister Sophia’s despair as they had been almost like twins in looks and temperament. Victoria doted them on them as she had their father and was made godmother to two of them – Victor Albert (named after the royal couple as was tradition), and the youngest girl Sophia.

As he aged, Duleep began to question

the legality of the treaty he had been forced to sign as a child, destroying his

relationship with Queen Victoria in the process. Eventually, he uprooted the

family with the intent of returning to the Punjab and triggering an uprising to

reclaim his throne. However, the family only got as far as Yemen before they

were apprehended by British troops and were returned to Britain. Unfaithful

throughout his marriage, Duleep had two more daughters with his mistress, Ava,

whom he later married and moved with them to France, abandoning his legitimate

family. Victoria’s love for Duleep is evident from the care and protection she

continued to offer to his surviving family, especially his youngest daughter,

Sophia, even after the disgrace of her father.

Sophia and

Victoria

Following her father’s abandonment, Sophia

was rescued by her godmother who sheltered the family on their return. The Queen

herself took over Sophia’s schooling when her mother died of alcoholism in 1887,

and Sophia was appointed a guardian in Brighton. Victoria hosted the Duleep

Singh sisters’ “Coming Out” ball at Buckingham palace, making a clear statement

that Sophia was welcome at court despite her father’s actions. When she came of

age in 1896, Sophia was gifted Faraday House – part of Hampton Court Estate –

by Queen Victoria and was even given her own key for Hampton Court Palace where

she used to walk her dogs in the grounds. Her elder sisters shared their

father’s animosity towards the crown, but Sophia and her brothers still adored

the Queen and remained loyal to the British.

Sophia the

Socialite

Sophia became one of the world’s first

international celebrities, well known for her royal connections on both sides of

the empire. She was a fashionista and splashed out on expensive cloths and

plush décor for her house. She was also a champion dog breeder, winning many

dog shows and carrying her beloved dogs with her wherever she went. She also

had a keen interest in sports and was the first woman in England to ride a bicycle

(much to the horror of conservative Victorian society who feared the freedom

women could gain from having an independent means of travel)! Sophia frequently

toured Europe, spending a great deal of time staying with her sister Catherine

in Germany (where she lived with her female lover, an interesting story in

itself!) Sophia’s was undoubtedly an opulent lifestyle filled with high society

and glamour, but she was prone to depression and anxiety and she continued to

struggle with her mental health throughout her life (unsurprising given her

tragic family history).

India

“Oh you wicked English, how I long for

your downfall…Ah India, awake and free yourself!”

Despite the family being explicitly exiled

from India, the Duleep Singh sisters risked everything to travel to India for the

first time to see the Delhi Durbar (a celebration of the coronation of Edward

VII). The British feared she would trigger a rebellion when crowds greeted her

with cries of: “We are with you, we will give you the world.” Ironically, it

was in India that Sophia first experienced racism from the British, who treated

her as a second-class citizen rather than the princess she was treated as under

the Queen’s protection in London. This trip transformed her view of the British

as she witnessed firsthand the racism with which Indians were treated and the

famine and suffering the British inflicted. She developed close bonds with

Indian nationalists, often sharing the stage with Gokhale & Lala Rajput Rai

who put the sisters on stage as symbols of resistance against the British. Her

sister Catherine decided to stay in India, but Sophia returned home to London

to fight the injustice she witnessed from within.

An Indian Princess

On

her return, Sophia made it her mission to protect the interests of India(ns) in

Britain. She visited her local Sikh temple regularly and attended many

diplomatic functions at the India Office. She supported the Indian Women’s

Education Association and the Lascars Club supporting Indian Seamen and sailors.

Her work in this area showed that despite her privileged position in British

society, Sophia was not ignorant of the class differences in experiences of

racism and discrimination faced by Indians and other colonial diasporas in Victorian

Britain and made a tangible effort to improve the lot of those less fortunate.

Sophia

paid for the education of her Indian family and returned to the country several

times to visit her sister and friends and to keep updated on the Indian

Independence movement. This resulted in an increasingly antagonistic

relationship with the India Office and the Royal Family following the death of

her Godmother Queen Victoria in 1901 as suspicions grew about her sympathy for

her father’s treatment under the British. However, her attentions would soon be

turned to a different cause closer to home.

Sophia the Suffragette

"The policeman was unnecessarily

and brutally rough and Princess Sophia hopes he will be suitably punished"

The cry of the Indian nationalists of

‘Awaz doh’ (‘Give us a voice’) had awoken a sense of dispossession in Sophia and

she began to hear the same cry from the increasingly active Suffragettes. Sophia

became an active member of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) and

was often seen selling The Suffragette newspaper outside Hampton Court (as

pictured here in 1913). She drove press carts bearing the heraldry designed for

her father by Prince Albert and once threw threw herself infront of the Prime

Minister’s car bearing a “Give women the vote” banner.

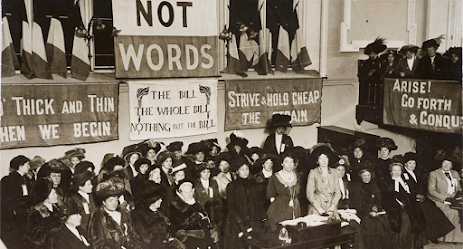

Above you can see

Sophia sharing a stage with the more famous Emmeline Pankhurst. Sophia and

Emmeline stood side by side on 'Black Friday', 18 November 1910: when over 300

suffragettes marched from Caxton Hall to Parliament Square and demanded to see

the Prime Minister. The protest was met with appalling scenes of police

brutality, leading to the deaths of two suffragettes. Sophia and Emmeline formed

a line in front of parliament, but Sophia broke through police lines to defend a

fellow suffragette from the violent assault of a police officer. She then

pursued the officer until she discovered his identification number and made a

formal complaint in which she demanded he be held accountable for the attack (he

wasn’t).

-----

“No vote, no census. As women do not

count, they refuse to be counted, and I have a conscientious objection to

filling in this form.’

Sophia also took part in the Suffragette boycott of the national census in 1911, her paper from which can be seen above.

She became a member of the member of the Women’s Tax

Reform League (WTRL), which campaigned on the principal – 'No Vote, No tax!'.

In 1911 and 1913 Sophia was summoned to court and fined £3 for keeping a

man-servant, five dogs and a carriage without licence. She refused to pay the

fine, stating: “When the women of England are enfranchised and the state

acknowledges me as a citizen I shall, of course, pay my share willingly towards

its upkeep." Consequently her possessions and jewellery were auctioned to cover the fees, but these were bought by

wealthy suffragettes and publicly returned to her in triumph.

World War One

In 1914, however, the Suffragette mission

took a back seat as women focussed on keeping Britain together during the first

world war. Sophia was part of the 10,000 strong Women's War Work Procession led

by Emmeline Pankhurst in 1915. Over one million Indian troops served overseas,

of whom at least 74000 died and another 67,000 were wounded. Sophia was keen to

emulate and help the thousands of Indians who were fighting for the Allied

Powers. Sophia also successfully petitioned to rescue her sister from Germany so

that she was not caught up in the war or attacked by the British, showing that

despite her radical views and actions Sophia still had powerful connections.

In 1916 Sophia raised money for the

Red Cross selling Indian flags with other Indian women, as part of the 'Our

Day' celebration of the anniversary of the British Red Cross. In 1918, as

Honourable Secretary of the YMCA War Emergency Committee, she organised 'India

Day' for the support of India's soldiers, providing them with 50,000 huts.

Again showing that she had no

delusions of grandeur and was willing to get her hands dirty, the Princess

visited and even nursed troops at Brighton Pavilion and other hospitals for

Indian soldiers. These soldiers were amazed to see the Princess in the flesh,

and she gave out mementoes of signed photographs and little ivory mirrors to

boost morale amongst the wounded.

India and World

War 2

Sophia would soon live to see another

world war and again did her best to support the country through it.

During the Second World War Sophia

moved to Buckinghamshire with her sister Catherine and they took in evacuees

from West London. Sophia had no children of her own and was devastated when

they returned to their mother after the war – although she was comforted by being

made godmother to her housekeeper’s daughter who she doted on for the rest of

her life.

Throughout WW2, Sophia made enemies of

the most powerful men in the Empire, including Winston Churchill and King

George V. Churchill often made disparaging comments about Indians. For example,

he told his Secretary of State for India, Leo Amery, that he "hated

Indians" and considered them "a beastly people with a beastly

religion". During the war, Churchill prioritised the stockpiling of food

for Britain over feeding Indian subjects during the Bengal famine of 1943 against

the advice of the Indian Viceroy. Under British rule, 30-35 million Indians

died of starvation (Tharoor 2016). Sophia was not afraid to point out these

painful truths and shine a mirror on the hypocrisy of the British’s “civilizing”

mission. This was viewed as ingratitude by the British elite, but further

endeared her to Indians in Britain and in India. She lived to see India gain

independence from the British in August 1947.

Death and legacy

“Too brown for a white man and too

white for a brown man, and far too much trouble for either”

Sophia never married or had children

of her own, but I believe she was more than content without a husband. She continued

her suffragette activities throughout her life (see above Sophia (left) and her

sister Catherine at a Suffragette dinner in 1937.) Princess Sophia died

peacefully in August 1948, aged 72. Her ashes were buried in India.

I believe that the greatest testament

to Sophia’s life lies in the following anecdote. When asked to interview for Who’s

Who, she gave just one line in answer. Under ‘interests’ she simply wrote: ‘The

advancement of women’.

Since learning of Sophia by chance at

an extra-curricular lecture in 2018, I have adored and admired her not only because

her life combines all my academic interests but because she is just such a

tangible and inspirational gal. Overcoming a tragic family life, mental health

struggles, racism, sexism, dispossession, institutional discrimination, social

isolation, and two world wars, I don’t see how anyone can fail to be impressed

by all she achieved and championed. Her story is a reminder of how far women

have come in such a short space of time – and also how far we still have to go

before women of colour are treated as equal citizens in Britain. It infuriates

me that I studied history until Advanced Higher level and that Sophia never once

featured in any of the lessons on the suffragettes, the war, or Victorian

Britain in general. This is as British as history gets. Today, there are at least

1.4 million people in the UK with Indian heritage (not including those of mixed

Indian and other ancestry), making them the largest ethnic minority population

in the country. The British Indian

community is the sixth largest in the Indian diaspora and the largest group of

British Indians are those of Punjabi origin, accounting for an estimated 45

percent of the British Indian population. We owe it to them to teach Sophia’s

story.

Sources

•

Alex von Tunzelmann (2017).

Indian Summer: The Secret History of the end of an Empire.

•

Anita Anand (2015). Sophia:

Princess, Suffragette, Revolutionary.

•

Anita Anand (2020). The

Patient Assassin.

•

Carly Collier (2019). Victoria

& Albert: Our Lives in Watercolour (RCT Exhibition Catalogue).

•

Christy Campbell (2010). The

Maharajah’s Box: An Imperial Story of Conspiracy, Love and a Guru’s Prophecy.

•

David Gilmour (2019). The

British in India: Three Centuries of Ambition and Experience & The

British in India: A Social History of the Raj

•

Patawant Ranjut Singh &

Jyoti M. Rai (2012). Empire of the Sikh’s The life and Times of Maharaja

Ranjit Singh.

•

Priya Atwal (2020): Royals

and Rebels; The Rise and Fall of the Sikh Empire

•

RCT collections website:

https://www.rct.uk/collection

•

Shashi Tharoor (2016). Inglorious

Empire: What the British Did to India.

•

Shrabani Basu (2017). Victoria

and Abdul: The Extraordinary True Story of the Queen’s Closest Confidant.

•

William Dalrymple &

Anita Anand (2018). Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World's Most Infamous

Diamond.

•

Yasmin Khan (2016) The

Raj at War: A People’s History of India’s Second World War

Comments

Post a Comment